Dates as data

Authors:Christie Bahlai, Aleksandra Pawlik

Contributors: Jennifer Bryan, Alexander Duryee, Jeffrey Hollister, Daisie Huang, Owen Jones, Ben Marwick, and Sebastian Kupny

Spreadsheet programs have numerous “useful features” which allow them to “handle” dates in a variety of ways.

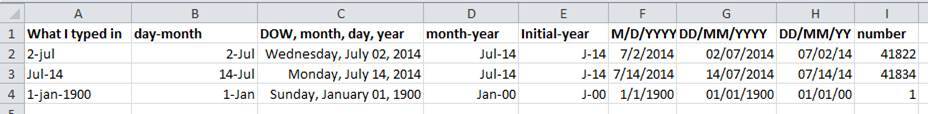

But these ‘features’ often allow ambiguity to creep into your data. Ideally, data should be as unambiguous as possible. The first thing you need to know is that Excel stores dates as a number- see the last column in the above figure. Essentially, it counts the days from a default of December 31, 1899, and thus stores July 2, 2014 as the serial number 41822.

(But wait. That’s the default on my version of Excel. We’ll get into how this can introduce problems down the line later in this lesson. )

This serial number thing can actually be useful in some circumstances. Say you had a sampling plan where you needed to sample every thirty seven days. In another cell, you could type:

=B2+37

And it would return

8-Aug

because it understands the date as a number 41822, and 41822 +37 =41859 which Excel interprets as August 8, 2014. It retains the format (for the most part) of the cell that is being operated upon, (unless you did some sort of formatting to the cell before, and then all bets are off)

Which brings us to the many ‘wonderful’ customizations Excel provides in how it displays dates. If you refer to the figure above, you’ll see that there are many, MANY ways that ambiguity creeps into your data depending on the format you chose when you enter your data, and if you’re not fully cognizant of which format you’re using, you can end up actually entering your data in a way that Excel will badly misinterpret. Worse yet, when exporting into a text-based format (such as CSV), Excel will export its internal date integer instead of a useful value.

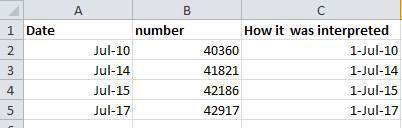

Once, I received a dataset from a colleague representing insect counts that were taken every few days over the summer, and things went something like this:

If Excel was to be believed, my colleague had been collecting bugs IN THE FUTURE. Now, I have no doubt this person is highly capable, but I believe time travel was beyond even his grasp.

Thus, in dealing with dates in spreadsheets, we recommend separating date data into separate fields, which will eliminate any chance of ambiguity.

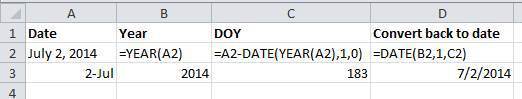

In my own work, I tend to store my dates in two fields: year, and day of year (DOY). Why? Because this is what’s useful to me, and there is practically no possibility for ambiguity creeping in.

The types of statistical models I build usually incorporate year as a factor, to account for year-to-year variation, and then I use DOY to measure the passage of time within a year.

So, can you convert all your dates into DOY format? Well, in excel, here’s a handy dandy guide:

Exercise: pulling month out of Excel dates

- In the

datasubdirectory there is an example dataset: a short list of species with one of the columns containing dates. - Extract month from the dates to the new column.

Note: Excel is unable to parse dates from before 1899-12-31, and will thus leave these untouched. If you’re mixing historic data from before and after this date, Excel will translate only the post-1900 dates into its internal format, thus resulting in mixed data. If you’re working with historic data, be extremely careful with your dates! Excel also entertains a second date system, the 1904 date system, as the default in Excel for Macintosh. This system will assign a different serial number than the 1900 date system. Because of this, dates must be checked for accuracy when exporting data from Excel (look for dates that are ~4 years off).

Previous: Common formatting mistakes by spreadsheet users. Next: Basic quality control and data manipulation in spreadsheets.